|

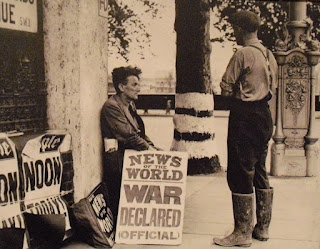

| Preparing for War - 1938 (author's photo) |

"This morning, the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that unless the British Government heard from them by 11 o'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such assurance has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany."

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain addressed the British people at 11:15 on that fateful Sunday morning and his words are well known now but reactions around the world varied greatly as might be expected.

In Berlin, the British ultimatum was read aloud to Hitler by Dr. Schmidt, the official translator at the German Foreign Ministry. The Fuhrer sat immobile and gazed in silence. After what seemed a long interval, he turned to Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, who was also present and asked "What now?" According to Schmidt, Hitler had a savage look to his face, as though implying that Ribbentrop had misled him as to the probable British reaction. Ribbentrop answered quietly "I assume that the French will hand in a similar ultimatum within the hour."

In Berlin, the British ultimatum was read aloud to Hitler by Dr. Schmidt, the official translator at the German Foreign Ministry. The Fuhrer sat immobile and gazed in silence. After what seemed a long interval, he turned to Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, who was also present and asked "What now?" According to Schmidt, Hitler had a savage look to his face, as though implying that Ribbentrop had misled him as to the probable British reaction. Ribbentrop answered quietly "I assume that the French will hand in a similar ultimatum within the hour."

In London, even before Chamberlain had spoken, the Royal Navy sent the simple cable "TOTAL GERMANY" to it's ships and bases around the world, followed that evening by a further signal "WINSTON IS BACK" advising, or perhaps warning the fleet that Winston Churchill had been reappointed to his First World War role as First Lord of the Admiralty.

|

| Advice on Shelters (author's photo) |

Barely had the Prime Minister finished speaking, when at 11:27 in London, the mournful note of the air raid sirens, which were to become so familiar over the coming almost six years, announced to the capital that an air raid was imminent. Many Londoners, perhaps remembering Stanley Baldwin's assertion that "The Bomber will always get through" reinforced by having read or seen the movie version of HG Wells' 'The Shape of Things to Come' doubtless felt that this might be the beginning of an apocalyptic future for London as outlined by the likes of Bertrand Russell, or indeed the British Air Staff, who in 1938 predicted that 3,500 tons of bombs could fall on London in the first twenty four hours of a future conflict, causing 58,000 fatal casualties and many more injured. Others were doubtless more sanguine but almost everyone was afraid to a greater or lesser degree, although most kept their fear well concealed. In fact, the alert was a false alarm, caused by a French aircraft which had stumbled into Britain's air defence system. The first air raids on London would not come until a year later and although the raids when they did come would naturally bring death and destruction, the consequences were never as remotely devastating as had been predicted. The 58,000 figure of fatalities confidently predicted for London in 1938, was only just exceeded (by 2,000) across the entire country for the duration of the war.

|

| The spectre of Poison Gas (author's photo) |

Around the World, the British Empire and Commonwealth followed suit - the idea of Britain as 'The Mother Country' seems quaint and outdated today but it was something that still held sway in 1939. Australia and New Zealand declared war immediately, with New Zealand Prime Minister Michael Savage memorably stating of Britain that "Where she goes, we go!" South Africa at first demurred from declaring war and wished to remain neutral, but the Government was defeated in a parliamentary vote and the new Prime Minister, Jan Smuts, declared war on Germany on September 6th. The Canadian Government followed on September 10th.

In Washington DC, President Roosevelt broadcast to the American people hours after the British and French declaration of war and although he had to tread carefully at this stage to preserve American neutrality, Roosevelt nailed his colours clearly to the mast in his intention to stand firm with the democracies of Europe.

"This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remains neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of the facts. Even a neutral cannot close his mind or his conscience."

As yet unknown to his listeners, the President had already resolved to recall Congress so that his Administration could seek a repeal of the arms embargo and at least passively support the democracies against the Nazi regime.

|

| Confirming the news (author's collection) |

Even at this early stage of the war, Hitler was anxious about possible American involvement and his anxiety must have been further increased when news reached him that the war had taken it's first casualties in the North Atlantic, when the liner Athenia was torpedoed by the U-30 at 19:43 that same evening. The vessel was carrying 1,103 passengers, including some 300 American citizens anxious to escape the war now overwhelming Europe and who were returning home via the liner's intended destination of Montreal.

Mindful perhaps of keeping America out of the war and convinced that Britain and France would soon be looking for a political solution anyway, Hitler had already ordered that passenger ships carrying passengers were to be allowed to proceed in safety, even if part of a convoy but Fritz Julius Lemp, in command of U-30 did not bother to check on the credentials of the Athenia and ordered the firing of a salvo of torpedoes at the defenceless liner. Lemp then compounded his error by surfacing and opening fire on the stricken vessel in an attempt to shoot away her wireless aerials. It was at this point, with lifeboats obviously being filled with passengers that the U-Boat commander realized that he had sunk a passenger ship both in violation of International Law and his Fuhrer's order but he made no attempt to atone for his error and merely submerged without offering any assistance.

The liner had in fact, sent out a distress signal and was remarkably still just about afloat by the time that rescue vessels arrived on the scene, although she sank later the following morning. The 118 persons killed were the first casualties of the Battle of the Atlantic and included 22 American citizens, which caused outrage in the United States and set the majority of public opinion in that country against the Germans from the outset.

Back in England, aside from the Royal Navy's instructions to the fleet, the other services were taking practical steps to take the war to Germany. At RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire that evening, six Hampden bombers of 89 Squadron under the command of Squadron leader Leonard Snaith took off to attack German warships at the great naval base at Wilhelmshaven. An earlier reconnaissance flight by a single Blenheim bomber from RAF Wyton had confirmed the presence of German warships but the failure of the aircraft's wireless to operate at 24,000 feet had caused a delay in reporting the fact until after it's return to base.

The raid, such as it was, was a fiasco; the crews had already been given strict instructions not to bomb civilian establishments, either houses or dockyards and therefore could only bomb the warships if they were at anchor in the harbour rather than alongside for fear of hitting buildings rather than the ships. As they approached Wilhelmshaven, the weather, already poor, became even worse and the cloudbase dropped to 100 feet. Not really knowing for sure where his squadron was, Snaith took the only decision open to him and turned his squadron for home, dumping their bombs into the sea en route. They eventually reached Scampton at 22:30 but fortunately everyone made it home on this occasion. Those on the follow up raids ordered the next day would not be so fortunate; of the fourteen Wellingtons and fifteen Blenheims despatched, five of the Blenheims were shot down and although they managed to land three bombs on the Admiral Scheer, all of these failed to explode. Ten of the Wellingtons became hopelessly lost and some dropped their bombs on the Danish city of Esbjerg, some 110 miles off target, where they killed two people. Clearly, the RAF had much to learn but at least had tried to take some offensive action.

|

| Churchill in defiant mood (IWM) |

The Army had already begun to implement plans for a British Expeditionary Force to be sent to France some ten hours before the declaration of war, when the passenger ship Isle of Thanet sailed from Southampton to Cherbourg with the first advance party of what was to become a sizeable force of over 300,000 men, the majority of whom would be evacuated from France less than a year later.

The conflict at sea was a shooting war from the outset but apart from this and some further costly efforts by the RAF in attempting to bomb German naval targets in daylight without fighter protection, the war was soon to settle down into a period of relative inertia known to the British as 'The Phoney War', the French as 'Drole de Guerre' ('Funny War') or in Germany as 'Sitzkrieg' ('Sitting War.')

This somewhat surreal period was typified by an approach to the war that seems farcical now - for example, when British MP Leo Amery proposed that the RAF drop incendiary bombs on the Black Forest, in order to destroy stocks of ammunition thought to be stockpiled there, he received the reply from Sir Kingsley Wood, Secretary of State of Air, that the Forest was 'private property' and therefore could not be attacked. Wood also stated that armaments factories could not be bombed for the same reason and that furthermore, such attacks might provoke the Germans to mount similar attacks on British factories. The activities of the RAF's bomber force was soon to be limited to dropping leaflets on German cities which no doubt had little effect on the civilian population other than increasing their supplies of scrap paper.

The Phoney War period was to end suddenly with the Norwegian Campaign in April 1940, one consequence of which was the downfall of Chamberlain's Government and it's replacement with a coalition Administration under Churchill, which saw the country through the dark days of the Fall of France and Low Countries, followed by the evacuations from Dunkirk and the Channel Ports to the defiance of the Battle of Britain and The Blitz and which would eventually see the country to victory in 1945.

Published Sources:

The Battle of the Atlantic - John Costello & Terry Hughes, Collins 1977

The Battle of Heligoland Bight 1939 - Robin Holmes, Grub Street 2009

BEF Ships before, at and after Dunkirk - John de S Winser, World Ship Society 1999

Bomber Boys - Patrick Bishop, Harper Press 2007

London at War 1939-1945 - Philip Ziegler, Pimlico 2002

The World at War - Mark Arnold-Foster, Collins 1973