Choosing one's favourite war movies is by definition, an extremely subjective process. Even deciding what actually constitutes a war film can become a matter of intense debate between friends. For example, should a documentary film be considered a true war movie, or does it have to be a star-studded feature or an epic with a 'cast of thousands' to be so classed?

Choosing one's favourite war movies is by definition, an extremely subjective process. Even deciding what actually constitutes a war film can become a matter of intense debate between friends. For example, should a documentary film be considered a true war movie, or does it have to be a star-studded feature or an epic with a 'cast of thousands' to be so classed?Recently, I was lucky enough to visit "Real to Reel", an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London that is devoted to the genre and which covers pretty well every aspect that you could imagine, from the very earliest film, The Battle of The Somme, a documentary actually made during the same year of the Allied offensive in 1916, right through to the modern day Kajaki as well as American Sniper both dating from 2014. The exhibition looks at the initial ideas for movies, the 'vision' of a director, the casting, as well as the physical and logistical difficulties in making an historically accurate depiction. Sometimes though, film makers get things horribly wrong; the execrable U-571 dating from 2000, ignored the historical fact that the Royal Navy captured the first Enigma coding machine and actually showed this as an entirely American feat of heroics. The film was debated in Parliament and rightly shunned by British veterans. The film makers were eventually shamed into inserting a disclaimer at the beginning of the movie to explain what really happened but by then the damage had already been done. Another example was Objective Burma! made in 1945 and which featured Errol Flynn leading American paratroopers defeating the Japanese in a conflict which in reality was almost exclusively a British and Commonwealth affair. The outrage caused at the time was widespead and the movie was actually banned in British cinemas shortly after it was released.

As might be expected, the exhibition features many excerpts from classic movies as well as many of the props and models used to ensure that the experience of watching these films remains realistic and authentic to the time. For example, we can see some of the uniforms and costumes worn by David Niven in A Matter of Life and Death, by George C Scott in Patton, and by Peter O'Toole in Lawrence of Arabia. Interestingly, whilst O'Toole was a strapping six footer, the real life TE Lawrence was a somewhat smaller 5 feet 5 inches tall, which demonstrates another issue facing film makers, that of casting their movies accurately. Amongst the models on display is one of the B-17 models used in Memphis Belle, the cable car from Where Eagles Dare and the submarine from Das Boot. Perhaps the most famous prop on display is that motorcycle from The Great Escape, a Triumph TT Special 650 disguised to look like a German machine, that Steve McQueen used and on which he performed many of his own stunts, although not the final leaps over the barbed wire, which was actually performed by a stunt double.

My own very enjoyable morning viewing the exhibition sparked off afresh the debate in my mind about the greatest war movies, so in the hope of sparking a whole new debate amongst the readership of this blog, I've decided to list my favourite ten war films, in no special order of merit and for no other reason except that I like them. Some are complete fantasies whilst some are almost documentary accurate. Believe me, I have had to murder some of my darlings in paring this list down to a mere ten but will cheat slightly by adding some 'honourable mentions' at the end. You will almost certainly disagree with some or all of my choices but then you do have the chance to make your own list through the comments page.

At 10, we start with Battle of Britain, a 1969 British film that is an extremely accurate depiction of the events of the summer and autumn of 1940, when the RAF handed the first serious defeat to the German war machine. The film stars Laurence Olivier, Trevor Howard, Michael Caine, Christopher Plummer, Robert Shaw, Susannah York and many others portraying a mixture of real people such as Lord Dowding, Sir Keith Park and Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory and thinly disguised fictional characters (for example, the Robert Shaw 'Skipper' character is loosely based on 'Sailor' Malan.) The film is also remarkable for it's flying sequences, being all shot using real aircraft in real time. There was no CGI available in 1969 and the film is all the better for it. The movie's flight consultant was Group Captain Hamish Mahaddie and he managed to gather together what was described at the time as the 35th largest air force in the world. The German aircraft were sourced largely from the Spanish Air Force and were adapted Spanish built CASA 111 bombers (almost identical to the Heinkel He111) and Buchon fighters, a Spanish version of the Bf109. The Spitfires and Hurricanes were mainly later marks that didn't fight in the Battle but which were carefully adapted to increase authenticity. The scenes of the London Blitz were filmed in St Katherine's Dock in London, at that time being redeveloped and with many of the old warehouses being earmarked for demolition in any case, with further filming taking place in Southwark and at the real life Aldwych Tube Station. I first saw this film shortly after release in 1969 with my Dad and some 47 years on, it remains one of my firm favourites.

Number 9 sees another film I first saw as a young lad - this time on tv - and which made a lasting impression upon me. This is The Cruel Sea, a 1953 production from Ealing Studios which itself is an adaptation of Nicholas Monsarrat's classic novel of the same name. Monsarrat himself served in the Royal Navy on North Atlantic, East Coast and Arctic convoy duties, so much of what we see in the film is based on his own experiences. The film stars Jack Hawkins as Commander Ericson of the fictitious corvette HMS Compass Rose and who in my opinion, gives the performance of his career. He is ably supported by Donald Sinden as Lieut. Lockhart (who is almost certainly Monsarrat), Denholm Elliott and Virginia McKenna, as well as a superbly unpleasant performance by Stanley Baker. Perhaps the most famous scene in the book features Ericson having to make an agonising decision when a U-Boat is detected directly beneath a group of survivors in the water. Having decided to attack, the men are blown to pieces in the ensuing depth-charge attack, with Ericson and his crew watching horrified at the sight of what they have done. Haunted by what has happened, Ericson gets himself helplessly drunk when Compass Rose puts into Gibraltar at the end of this voyage. The little corvette has already rescued many survivors of other sunken ships and some of them try to console Ericson by telling him that they owe him their lives and that he should feel no remorse towards the men who died in the water - "The men you had to kill" - as one of them says somewhat undiplomatically. He is joined by Lockhart who has also been drinking and who also tries to console Ericson by taking the blame for identifying the contact as a U-Boat. Ericson tearfully looks at Lockhart and merely replies that "No one murdered those men, it's the war, the whole bloody war."

At 8, we have another movie about the Battle of the Atlantic, albeit a much more recent example and one which looks at things from a German point of view. The 1981 film Das Boot is a superbly claustrophic piece of work from the director Wolfgang Petersen based on a novel by Lothar Gunther Buchheim which tells the story of U-96 through the eyes of a reporter placed on board to make a propaganda piece about the crew and life on board a submarine at war. The all German cast is led by Jurgen Prochnow playing the cynical, veteran commander of the boat (as all submarines are called by their crews), supported by Klaus Wennemann playing the equally veteran Chief Engineer and Herbert Groenemeyer in the role of the journalist, Leutnant Werner. The movie highlights tensions between the newer, Nazi Party supporting members of the crew such as the First Watch Officer and the older, more seasoned veterans. As the submarine moves in to attack a British convoy in filthy weather, their periscope is spotted by a Royal Navy destroyer and the U-Boat (and the audience) endures what must be the most accurate depiction of a depth-charge attack ever put on film. The boat is shaken, lamps and gauge glasses explode and one can almost feel the nerves of the crew being jangled with each explosion but the wily captain eventually manages to extricate the submarine with only light damage. Eventually, the submarine torpedoes a British oil tanker which the crew think has been abandoned. To their horror, when the torpedoes strike, crew members emerge from the stricken ship and dive into the water, which is itself now ablaze from the spilled cargo of the tanker. Under strict orders not to pick up survivors, the submarine backs off, leaving the screaming men to their fate. Further adventures follow and the submarine is ordered to attempt to break into the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar. First though, the submarine makes a clandestine refuelling stop in neutral Vigo, Spain to replenish from an interned German merchant ship located there. The Captain has radioed in advance for the Chief Engineer to be relieved in order that he may return to his family in the bombed city of Hamburg and has also requested that the journalist be allowed home as well but the request is denied and the submarine attempts to enter the Mediterranean. The U-Boat is relentlessly depth charged by the British in another hair raising sequence before finally sinking to the bottom. Makeshift repairs are effected before the submarine limps back to base in La Rochelle with a severely injured crewmember on board. The ending of the movie is both moving and tragic which echoes truthfully the fate of the vast majority of the German U-Boat men. Bravery was not restricted to the Allied side and this film is a fine testament to those intrepid submariners.

A castle known as the Schloss Adler features at number 7 in the 1968 movie Where Eagles Dare, based on the novel by Alistair MacLean and which contains many of the author's trademarks, such as the heroes fighting against seemingly overwhelming odds as well as there being a traitor (or traitors) within the closer circles of the heroes, with the main traitor not being unmasked until almost the end of the film. The action features around the rescue attempt of one General Carnaby, a senior American planner behind the forthcoming Allied invasion of Europe. His aircraft is shot down and Carnaby is taken to the castle, where he is to be interrogated, if necessary by the use of Scopalomene, a 'truth' drug. A crack team of British commandos is assigned to rescue him, led by Richard Burton, as Major Smith and Clint Eastwood, an American Ranger officer seconded to the team. The casting of Eastwood ensured that the film would do well in America and was also a central point of the plot of the movie. The team eventually infiltrate the castle, despite losing two of their number in mysterious circumstances and meet up with two female operatives working under deep cover. Once in the castle, Smith allows himself to be captured and reveals to the others that he is in fact, a double agent and exposes three other members of the team, Thomas, Berkeley and Christiansen, who the Germans are convinced are their men, as being British agents. If you're confused, one only has to look at Eastwood's expression whilst all this is going on, to realise that you're not alone! It turns out that Carnaby isn't Carnaby at all but is merely an American actor, Cartwright Jones, planted to force all of this out into the open - Burton isn't a German spy and the three traitors really are British traitors working for the Germans, now fully exposed. An incredible escape from the castle now takes place, with the four survivors plus Cartwright Jones seemingly accounting for hundreds of German troops as they make for the local Luftwaffe base. Once aboard a plane and heading home, the final traitor unmasking takes place in dramatic circumstances - I won't reveal any more in case you're one of the handful of people who have never seen this often shown movie. An absolute classic!

So far, all of my favourites have taken place in World War Two, not so number 6, which sees us during an earlier conflict, one of Britain's many colonial wars fought throughout her history. This is Zulu, a 1964 re-telling of the events at Rorke's Drift, a missionary station and makeshift Field Hospital in January 1879, in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Isandlwana, a crushing British defeat. The film stars Stanley Baker, Jack Hawkins, Nigel Greene and Michael Caine in his first major starring role. Baker, a proud Welshman, became interested in becoming involved with the film when shown an account of the battle, in which eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the predominently Welsh defenders of Rorke's Drift, written by the historian John Prebble. Prebble later co-wrote the screenplay with Cy Endfield, who also directed the film as well as co-producing it with Baker. The 24th Regiment of Foot (the South Wales Borderers) along with a handful of others at the Field Hospital were around 150 strong but managed to fend off attack after attack from seemingly overwhelming numbers of Zulu warriors. The actions are shown in great detail and the relationships between the various defenders are brought to light, although there are some inaccuracies from real life. For example, we see Private Henry Hook portrayed by James Booth as a malingering, heavy drinking layabout, when in reality Hook was a model soldier and teetotaller. This portrayal of him caused his daughter to walk out of the film's premiere in disgust. Conversely, Corporal Allen (played in the movie by Glyn Edwards of later 'Minder' television fame) is shown as a model soldier, when in reality he had just been demoted to Corporal due to drunkeness. Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne, brilliantly played by Nigel Greene, is shown as a battle hardened veteran soldier, when in fact he was just 24 years of age and was at the time, the youngest Colour Sergeant in the British Army. A curiosity in the film is the appearance of Chief Buthelezi, playing his own uncle King Cetschwayo kaMpande. Despite the inaccuracies described earlier, this is a classic war movie, which survives the test of time and which is still shown frequently.

A castle known as the Schloss Adler features at number 7 in the 1968 movie Where Eagles Dare, based on the novel by Alistair MacLean and which contains many of the author's trademarks, such as the heroes fighting against seemingly overwhelming odds as well as there being a traitor (or traitors) within the closer circles of the heroes, with the main traitor not being unmasked until almost the end of the film. The action features around the rescue attempt of one General Carnaby, a senior American planner behind the forthcoming Allied invasion of Europe. His aircraft is shot down and Carnaby is taken to the castle, where he is to be interrogated, if necessary by the use of Scopalomene, a 'truth' drug. A crack team of British commandos is assigned to rescue him, led by Richard Burton, as Major Smith and Clint Eastwood, an American Ranger officer seconded to the team. The casting of Eastwood ensured that the film would do well in America and was also a central point of the plot of the movie. The team eventually infiltrate the castle, despite losing two of their number in mysterious circumstances and meet up with two female operatives working under deep cover. Once in the castle, Smith allows himself to be captured and reveals to the others that he is in fact, a double agent and exposes three other members of the team, Thomas, Berkeley and Christiansen, who the Germans are convinced are their men, as being British agents. If you're confused, one only has to look at Eastwood's expression whilst all this is going on, to realise that you're not alone! It turns out that Carnaby isn't Carnaby at all but is merely an American actor, Cartwright Jones, planted to force all of this out into the open - Burton isn't a German spy and the three traitors really are British traitors working for the Germans, now fully exposed. An incredible escape from the castle now takes place, with the four survivors plus Cartwright Jones seemingly accounting for hundreds of German troops as they make for the local Luftwaffe base. Once aboard a plane and heading home, the final traitor unmasking takes place in dramatic circumstances - I won't reveal any more in case you're one of the handful of people who have never seen this often shown movie. An absolute classic!

So far, all of my favourites have taken place in World War Two, not so number 6, which sees us during an earlier conflict, one of Britain's many colonial wars fought throughout her history. This is Zulu, a 1964 re-telling of the events at Rorke's Drift, a missionary station and makeshift Field Hospital in January 1879, in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Isandlwana, a crushing British defeat. The film stars Stanley Baker, Jack Hawkins, Nigel Greene and Michael Caine in his first major starring role. Baker, a proud Welshman, became interested in becoming involved with the film when shown an account of the battle, in which eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the predominently Welsh defenders of Rorke's Drift, written by the historian John Prebble. Prebble later co-wrote the screenplay with Cy Endfield, who also directed the film as well as co-producing it with Baker. The 24th Regiment of Foot (the South Wales Borderers) along with a handful of others at the Field Hospital were around 150 strong but managed to fend off attack after attack from seemingly overwhelming numbers of Zulu warriors. The actions are shown in great detail and the relationships between the various defenders are brought to light, although there are some inaccuracies from real life. For example, we see Private Henry Hook portrayed by James Booth as a malingering, heavy drinking layabout, when in reality Hook was a model soldier and teetotaller. This portrayal of him caused his daughter to walk out of the film's premiere in disgust. Conversely, Corporal Allen (played in the movie by Glyn Edwards of later 'Minder' television fame) is shown as a model soldier, when in reality he had just been demoted to Corporal due to drunkeness. Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne, brilliantly played by Nigel Greene, is shown as a battle hardened veteran soldier, when in fact he was just 24 years of age and was at the time, the youngest Colour Sergeant in the British Army. A curiosity in the film is the appearance of Chief Buthelezi, playing his own uncle King Cetschwayo kaMpande. Despite the inaccuracies described earlier, this is a classic war movie, which survives the test of time and which is still shown frequently.

We move forward to the First World War for our next entry, which is number 5 in my list. Lawrence of Arabia is a 1962 epic depicting the life and actions of TE Lawrence, directed by David Lean from an original screenplay by Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson, based on Lawrence's own autobiographical account of his wartime service, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. The movie won seven Academy Awards and stars Peter O'Toole (in his first major role), Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Omar Sharif, Anthony Quinn, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains and Jose Ferrer in a brief but memorable role. The film opens with Lawrence's death in a motorcycle accident and subsequent memorial service and so is almost entirely shot in flashback. The movie depicts Lawrence's actions in the Arabian Peninsular, his emotional struggles with the violence inevitable in war and his divided loyalties between Britain and his new-found friends and comrades from the various Arab tribes. The performance of every actor is remarkable and the production values are truly epic, as is the length of the film at 227 minutes. In cinemas, it was shown in two halves with an intermission and the DVD version of the film is also presented in the same way. The film's musical score by Maurice Jarre is also a classic and the film continues to be screened regularly to this day.

Another movie about the First World War is one that is not seen so frequently but which is still worthy of mention and features at number 4 in my list. Paths of Glory dates from 1957 and tells the story of an impossible attack by French soldiers on a German defensive feature known as 'The Anthill' which is forced upon the reluctant 701st Regiment and it's commander Colonel Dax, played by Kirk Douglas, by the ambitious General Mireau, played by George Macready. The depiction of the attack is brilliantly directed by Stanley Kubrick and shows the full horror of the attack, which begins to run out of steam. Desperate for the attack to succeed, Mireau orders his artillery to fire on his own men to force them forward but the attack fails, as predicted by Colonel Dax. To try and deflect the blame, Mireau selects one hundred men to be court martialled, although he is persuaded by his Commanding General Broulard to reduce this number to three. Dax, a lawyer in civilian life, defends the men at the Court Martial but the outcome is a foregone conclusion and the men are duly executed as an example to the other troops. The morning after the execution, Mireau is informed by Broulard that he is to be investigated for giving the order to fire on his own troops. Broulard then offers Dax Mireau's position, assuming that he is merely another ambitious officer. Dax refuses and when rebuked by Broulard for his misplaced idealism, Dax is disgusted and calls his superior a "degenerate and sadistic old man." The movie was based on the true story of four French soldiers executed in 1915 in similar circumstances and must have struck a raw nerve in France, as the authorities there banned the film's release until 1975.

We return to the Second World War for number 3 in the form of Ice Cold in Alex, which dates from 1958. The 'Ice Cold' in question is a cold beer and the 'Alex' is Alexandria and as this was another film that I originally watched with my Dad, himself a veteran of the North African campaign, it is another movie for which I have great affection. Almost all of the film takes place on a journey across the desert in an ambulance escaping from Tobruk to Alexandria ahead of the German advance. Captain Anson, played by John Mills, is a battle fatigued alcholic, whilst Sergeant Major Tom Pugh, played by Harry Andrews is the archetype of the reliable British NCO. Their passengers are two nursing sisters, Diana Murdoch and Denise Norton played by Sylvia Sims and Diane Clare. Along the way, they pick up a mysterious South African Captain Van der Poel, played by Anthony Quayle. They are twice stopped by elements of the Afrika Korps and when the ambulance is machine gunned in the first attack, Sister Norton is fatally wounded. The suspicions about Van der Poel are heightened when he twice speaks to the Germans privately, who on both occasions allow them to continue with the two nurses, having disguised the fact that Norton is in fact already dead. Anson is convinced that the South African is hiding a radio transmitter in his back pack, and they startle him in the Qattara Depression (an unstable area of quicksands and searing heat) whilst he is using the radio. With the South African trapped in the quicksands, they rescue him without revealing that they have worked out that he is a German spy. Having eventually reached Alexandria and the long awaited ice cold beers, the Military Police, alerted earlier by Anson, enter the bar to arrest Van der Poel, or Hauptmann Otto Luz as he really is. The famous scene in the bar was shot using real beers and for various reasons required fourteen takes, by which time John Mills was almost falling off the bar stool!

At 2, we take a look at the American "Mighty Eighth" Air Force in England during World War Two in the form of Twelve O'Clock High, a 1949 offering from Director Henry King. Starring a young Gregory Peck and ably supported by Dean Jagger, who won an Academy Award for his performance as Lieut Colonel Harvey Stovall. The film begins in post-war London, when the now retired Stovall spies a battered Toby Jug in an antique shop window and recognises it as an old mascot item from their former base at the fictitious RAF Archbury. He decides to revist the now abandoned airfield, which is gradually returning to agricultural use. The film then goes to flashback and we see B-17s returning from a mission in 1942 and concentrates on one bomber in particular. The crew are clearly traumatised from their experiences, the co-pilot vomits and explains that he has had to fight for two hours to regain control from his captain, who has had the back of his head shot off but who was still conscious. The severed arm of another airman is also removed from the aircraft. The following day, twenty eight airmen ask to be excused from their next mission, with the Squadron's Medical Officer privately asking "How much can a man take?" The Squadron Commander Keith Davenport, played by Gary Merrill, is relieved of his duties as he is felt to be getting too close to his men and he is replaced by Brigadier Frank Savage, played by Peck. Most of the film is about Savage's efforts to rebuild morale through various means and how the men under his command, who initially despise him for pushing them so hard, gradually identify with him and what he is trying to achieve. Savage pushes himself as hard as his men and refuses to be taken off active duty. The question asked earlier in the film "How much can a man take?" is apparently answered on the day of the squadron's first daylight raid on Berlin when Savage cracks and cannot physically haul himself into the cockpit of his B-17. The mission is led by another pilot whom Savage had previously 'busted' from Air Exec to an aircraft commander. Whilst the mission is in progress, Savage is in an almost catatonic state and only comes back to life once the squadron returns safely to Archbury. This movie is unusual for its time as it looks closely at the psycholological aspect of servicemen in wartime and deserves it's occasional screenings on television.

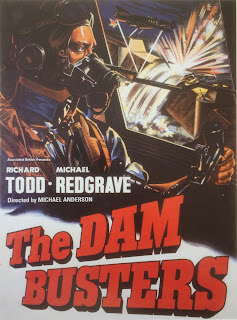

My own number 1 is another air related movie and is comes from the classic British period in the 1950s, when the Second World War was still fresh in many people's minds and experiences. The Dam Busters dates from 1955 and tells the story of the bombing of the Ruhr Dams and the development of the so-called Bouncing Bomb by the engineer and inventor Barnes Wallis, played in the film by Michael Redgrave. The bomb has to be delivered at low height by specially adapted Lancaster bombers and so a new unit is formed in RAF Bomber Command. 617 Squadron is commanded by Guy Gibson, who is portrayed in the film by Richard Todd, himself a World War Two airborne veteran and a stalwart of many British war movies of the 50s and early 60s. The film is a fairly faithful re-telling of the story which skilfully interweaves the trials and tribulations of Wallis against bungling bureaucrats in getting the weapon perfected in time and of Gibson in first forming the squadron and then the relentless training, made more difficult through Gibson not being allowed, for security reasons, to reveal the nature of the squadron's target until shortly before the mission. The night of the mission is portrayed fairly accurately, although it does somewhat gloss over the failure to breach the Sorpe Dam and concentrates on the two successful breaches of the Mohne and Eder Dams. The end of the movie is extremely poignant when Wallis learns that eight of the Lancasters have been shot down and tells Gibson that he would never have gone ahead with the idea if he'd known all of those crews were going to be killed. Gibson tries to console him by saying that even if they'd known what was going to happen that they would still have flown but finishes by telling Wallis that he can't go to bed yet as "I have some letters to write first." Richard Todd later said that he found that particular scene and that line quite hard work, as he had had to write real letters to the wives and loved one of those killed in action, so this really was a case of art imitating life.

So there are my ten war films; it has been an extremely difficult task to whittle down my list to a mere ten. It has meant leaving out some of my other favourites and consequently there is no room for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, San Demetrio: London, A Matter of Life and Death, The Colditz Story, The Way Ahead, The Way to the Stars, The First of The Few, Dunkirk, Bridge on the River Kwai, We Dive at Dawn and Went The Day Well? from the classic British era of war films. Neither is there space for The Longest Day, Patton, Von Ryan's Express, The Great Escape or Tora! Tora! Tora! from the American epics. Coming slightly more up to date, it has meant that Memphis Belle, Saving Private Ryan and A Bridge Too Far all miss out, as does the German made masterpiece, Downfall. It isn't just Second World War films that have been omitted out as I haven't been able to include the Vietnam movies Apocalypse Now or Platoon nor Black Hawk Down from a more recent conflict in Somalia, as well as the Napoleonic War films Waterloo or Master and Commander. As I have concentrated solely on feature films, there is no place for any of the superb documentaries made about the Second World War, such as The True Glory, Western Approaches or Desert Victory.

These are all fabulous pieces of work and whilst it might seem criminal to leave out at least some of those mentioned, I only allowed myself to choose ten.

As mentioned earlier, I'd really like to hear your choices and your reasons - it may be like me you have a leaning for the classic British movies of the 1940s and 50s, you might be younger and will have chosen some more recent offerings but please let me know your thoughts in the comments section. Leave a name rather than an anonymous selection and please be polite about my choices and those of others. Enjoy your film watching!

"Real to Reel" is on at the Imperial War Museum London until 8 January 2017. Tickets cost £10.00 (free if you're an IWM Member) and can be purchased via the IWM website or on the day at the Museum's Information Desk.

The Blitzwalker Ten

Battle of Britain - 1969, MGM Studios - Director: Guy Hamilton

The Cruel Sea - 1953, Ealing Studios - Director: Charles Frend

Das Boot - 1981, Bavaria Film - Director: Wolfgang Petersen

Where Eagles Dare - 1968, Warner Bros - Director: Brian G Hutton

Zulu - 1964, Diamond Films - Director: Cy Endfield

Lawrence of Arabia - 1962, Columbia Pictures - Director: David Lean

Paths of Glory - 1957, United Artists - Director: Stanley Kubrick

Ice Cold in Alex - 1958, Associated British - Director: J Lee Thompson

Twelve O'Clock High - 1949, Twentieth Century Fox - Director: Henry King

The Dam Busters - 1954, Associated British - Director: Michael Anderson

So there are my ten war films; it has been an extremely difficult task to whittle down my list to a mere ten. It has meant leaving out some of my other favourites and consequently there is no room for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, San Demetrio: London, A Matter of Life and Death, The Colditz Story, The Way Ahead, The Way to the Stars, The First of The Few, Dunkirk, Bridge on the River Kwai, We Dive at Dawn and Went The Day Well? from the classic British era of war films. Neither is there space for The Longest Day, Patton, Von Ryan's Express, The Great Escape or Tora! Tora! Tora! from the American epics. Coming slightly more up to date, it has meant that Memphis Belle, Saving Private Ryan and A Bridge Too Far all miss out, as does the German made masterpiece, Downfall. It isn't just Second World War films that have been omitted out as I haven't been able to include the Vietnam movies Apocalypse Now or Platoon nor Black Hawk Down from a more recent conflict in Somalia, as well as the Napoleonic War films Waterloo or Master and Commander. As I have concentrated solely on feature films, there is no place for any of the superb documentaries made about the Second World War, such as The True Glory, Western Approaches or Desert Victory.

These are all fabulous pieces of work and whilst it might seem criminal to leave out at least some of those mentioned, I only allowed myself to choose ten.

As mentioned earlier, I'd really like to hear your choices and your reasons - it may be like me you have a leaning for the classic British movies of the 1940s and 50s, you might be younger and will have chosen some more recent offerings but please let me know your thoughts in the comments section. Leave a name rather than an anonymous selection and please be polite about my choices and those of others. Enjoy your film watching!

"Real to Reel" is on at the Imperial War Museum London until 8 January 2017. Tickets cost £10.00 (free if you're an IWM Member) and can be purchased via the IWM website or on the day at the Museum's Information Desk.

The Blitzwalker Ten

Battle of Britain - 1969, MGM Studios - Director: Guy Hamilton

The Cruel Sea - 1953, Ealing Studios - Director: Charles Frend

Das Boot - 1981, Bavaria Film - Director: Wolfgang Petersen

Where Eagles Dare - 1968, Warner Bros - Director: Brian G Hutton

Zulu - 1964, Diamond Films - Director: Cy Endfield

Lawrence of Arabia - 1962, Columbia Pictures - Director: David Lean

Paths of Glory - 1957, United Artists - Director: Stanley Kubrick

Ice Cold in Alex - 1958, Associated British - Director: J Lee Thompson

Twelve O'Clock High - 1949, Twentieth Century Fox - Director: Henry King

The Dam Busters - 1954, Associated British - Director: Michael Anderson