|

| Bernard Law Montgomery (IWM) |

In early November 2013, I had the pleasure of guiding Bobbie and John Kinnear from Santa Barbara, USA on a private walk around Westminster’s wartime past. One of the pleasures of guiding is that one often meets the most interesting people and it was clear during our conversations both via email in planning the tour and whilst actually walking the ground that my clients not only knew their subject but also had a fascinating family connection with one of the major figures of World War Two, Bernard Law Montgomery.

Bobbie’s late father, Richard E Evans, was born in 1919 and after graduating from the University of Tennessee in 1939, won a local contest sponsored by the Tennessee Air National Guard for free pilot training. Later that year, he joined the Army Air Corps and trained on the Boeing Stearman biplane, before commencing his training on the then new B-17, a large four engine bomber, designed to deliver a large bomb load over long ranges, whilst at the same time being able to defend itself as part of a larger formation. In 1941, Evans became an instructor on the B-17 and following the USA’s entering of the war at the end of 1941, he attempted to get himself posted to England as part of the fledgling Eighth Air Force but was turned down owing to his experience as an instructor.

In January 1943 however, he was able to convince Colonel Fay Upthegrove, who was taking the 99th Bombardment Group to North Africa, into taking Evans along as one of his senior pilots and on the 20th of that month, the group flew to North Africa.

Captain Evans was part of 346th Bomb Squadron, 99th Bombardment Group, which formed

part of the 12th Air Force in the North African Theatre of Operations, based in

Algeria. At this time, 12th Air Force was operating in support of Allied land forces who were striving to eject Axis forces from North Africa. The Supreme Allied Commander was the then relatively little known Lieut-General Dwight D Eisenhower and one of his subordinate Army Commanders was the victor of El Alamein, Bernard Law Montgomery, or ‘Monty’ as he was universally known to the British, serviceman and civilian alike. Monty had given Britain her first major land victory over the Wehrmacht and had achieved this unaided, with British and Empire manpower alone.

This was an important victory, not only from a strategic point of view but also

politically. The British effort in the war was now to be steadily overshadowed

by the increasingly massive effort from the USA, both in manpower and industrial might, so it was vital to show our American allies that the British Army could beat the German war machine and that the British would not be ‘fighting to the last drop of American blood’ as some cynics on both sides of the Atlantic would believe. Monty, supremely confident in his own ability to the point of conceit, was just the man to provide this victory, although he was to prove almost as difficult a subordinate to Ike as he was an enemy to Rommel.

So, when Captain Evans was summoned to Colonel Upthegrove’s office, he could have

had no idea that his life as an American officer was to become intertwined, for the next few months at least, with Britain’s great hero. Captain Evans had flown 27 missions out of a possible full combat tour of 50 or even 60 missions, so a return home was hardly on the agenda. Neither was a promotion to Major, so Evans must have been wondering what he had done to warrant this summons to his senior officer. The prospect of meeting his C.O. held few worries for Evans, for he knew that he had done nothing wrong and that Colonel Upthegrove, or ‘Uppie’ as he was informally known behind his back, was a decent and fair man, who would not be summoning him for petty or trivial reasons.

On arriving at his C.O.’s tent that passed as an office, Evans was soon put out of

his misery and must have been astounded when he read his orders:

“…by order of General

Eisenhower’s Supreme Allied Headquarters, Algiers, through General Doolittle’s

Twelfth Air Force Headquarters, Constantine, Algeria.”

“Captain Richard E Evans, AO-397378,

99th Bombardment Group, 12th Air Force, North Africa, ETO, is hereby relieved

of his current duty assignment, is transferred to British 8th Army, and is

directed to report without delay to The Army Commander, General Sir Bernard Law

Montgomery.”

“A combat ready B-17 with full ammo and combat

aircrew will be assigned to Captain Evans for the period of this duty.”

|

| The All American - another B17E from 99th Bomb Group |

Evans was astonished by these orders and this astonishment was transparent enough to

assure Uppie that he had not been pulling a ‘fast one’ behind the Colonel’s back in order to escape further combat operations. Upthegrove had initially wondered whether Evans had family connections with Doolittle, Eisenhower, or even Monty, so he was as confused as Evans as to how and why his name had been pulled from the hat.

Evans next task was to select a crew. This was a simple task as he instinctively chose the men with whom he had been flying since bringing his B-17 across from the States; these were men that he trusted with his life and it would have been unthinkable for him to have chosen any other crew. Evans impressed upon his crew the nature of their assignment and also informed them what Uppie had told them – not to allow any harm to come to their illustrious passenger, otherwise none of them, Evans, his crew or Upthegrove, would ever hear the last of it!

Evans was mystified as to why Montgomery, a British General, should require the

services of a B-17, an American aircraft, complete with crew and although the great man himself was to explain the reason personally to Evans in due course, perhaps now is a good time to put the record straight.

Eighth Army had captured Sfax on 10th April and at a previous meeting with Ike’s Chief

of Staff, General Walter Bedell Smith, Monty had undertaken to capture this city no later than 15th April. Smith had told Monty that if this could be achieved, then General Eisenhower would give Monty anything he asked for. Monty, taking Smith to his word said that he would like the services of a B-17 aircraft, complete with crew for his personal use. Smith agreed, thinking that this was a semi-jocular remark by Monty. The British General however, was not well known for his sense of humour and was deadly serious; he realised that flying in a combat zone was a hazardous occupation and had hitherto been using a twin engine DC3 aircraft. Reliable enough, but unarmed and vulnerable to attack; a B-17 with four engines would give him greater comfort and reliability and would also be able to defend itself against any Germans who had gotten wind of Monty’s travel arrangements.

So, when Sfax was duly taken ahead of schedule, Monty insisted that the bet, however light heartedly it had been taken by Smith, be ‘paid up.’ Eisenhower, being the great and honourable man that he was, realised that Monty was being serious and supplied the aircraft on 16th April, which is where Captain Evans and his crew came in!

|

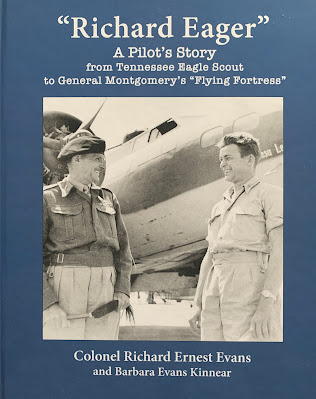

| Monty inspects 'his' crew - Richard E Evans on left (Bobbie Kinnear) |

It is possible that the seeds of Monty’s unpopularity in some American quarters

were sewn with this incident. Eisenhower was beginning to recognise that in Monty he had a great General but another ‘Prima Donna’ to rank alongside Patton to cope with. Monty’s ‘bet’ also got him into hot water with his British superior officer; General Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who reminded Monty that as far as Ike was concerned, the whole thing was a joke that had gotten out of hand. Brooke also pointed out that the RAF could have supplied Monty with a modern four engine aircraft, such as a Lancaster or a Halifax, to which Monty replied that indeed the RAF could have – but hadn’t, despite his repeated requests!

Monty’s own theory on the matter was that Bedell Smith had omitted to mention to Ike

his initial promise of an aircraft to Monty and that when the British General had approached Eisenhower demanding ‘his’ aircraft, this was actually the first that he had heard of the proposal. This explanation is plausible and to someone like Monty, who had little in the way of social or diplomatic skills, it was all something quite simple – a bet had been made and it was time to pay up!

All this was unknown to Captain Evans and his crew as they flew into Tripoli in the ‘new’ B-17 that had been selected for this strange assignment. The bomber was not actually new at all but rather an elderly (by B-17 standards) machine named Theresa Leta. Evans never did find out exactly after whom the bomber had been named but it seemed bad luck to change it, especially when he discovered that this was the very bomber that General James Doolittle had flown down from the UK to North Africa during the Allied invasion of that continent. Theresa Leta was a B-17E; not the latest model but still a fine aircraft for a General Officer to have as his personal transport.

Later, Monty would write Evans a personal explanation of the reasons behind his getting hold of a B-17 which read as follows:

"The Fortress aircraft was given to me by General Eisenhower in April 1943, after I had captured SFAX. He came to visit me at my Army HQ shortly after the Battle of MARETH; it was the 2nd April and I was busy preparing to attack the AKARIT position and then to burst through the GABES Gap and out into the plain of central Tunisia.

|

| Part of Monty's explanatory letter to Evans (Bobbie Kinnear) |

I told General Eisenhower that when I had captured SFAX there would be need for considerable co-ordination between the action of the Allied Armies in Tunisia and this might mean a good deal of travelling about for me. I asked him if he would give me a Fortress (B17); the splendid armament of these aircraft makes an escort quite unnecessary and I would be able to travel at will and to deal easily with any enemy opposition. I said I would make him a present of SFAX by the middle of April and if he would then give me a Fortress it would be magnificent. I captured SFAX on 10th April and the Fortress was sent to me a few days later.

I have travelled many miles in it and it has saved me much fatigue. I have no hesitation in saying that having my own Fortress aircraft, so that I can travel about at will, has definitely contributed to the successful operations of the Eighth Army. I cannot express adequately my gratitude to General Eisenhower for giving it to me; he is a splendid man to serve under and it is a pleasure to be under his command.

The crew of my Fortress are a fine body of officers and men and their comfort and well-being is one of my first considerations.

It is a very great honour for a British general to be flown about by an American crew in an American aircraft and I am very conscious of this fact.

BL Montgomery

General

Eighth Army"

Upon landing at Tripoli, Theresa Leta was met by a British lorry, the driver of which

gestured to Evans to follow him, and guided by their British Allies, the B-17 lurched across the steel planking to it’s designated parking place, where Captain Evans and his crew were met by a moustachioed, very senior looking British General, who turned out to be the irrepressible General Francis De Guingand, known to all and sundry as “Freddie”, the immensely popular (and very able) Chief of Staff to General Montgomery himself. This was quite a welcome but the friendly British officer soon put Evans at ease and promptly invited the Captain and his crew to the following day’s victory celebrations which were to be attended by no less a dignitary than King George VI himself!

|

| General Francis 'Freddie' De Guingand (IWM) |

After explaining the whereabouts of the crew’s accommodation and the arrangements for

parking the B-17, Evans was whisked off to visit the great man himself outside his headquarters tent. Up until now, Evans had hardly had time to be nervous but his disposition could hardly have been improved when upon being introduced to his new pilot, Monty stared hard and uncomprehending at the Captain, before turning on his heels and walking straight into his tent without uttering a single word to the now bewildered American officer!

With great presence of mind, Captain Evans decided to follow Monty into his tent to

make certain he had taken on board his arrival and upon entering the tent, Evans found the Eighth Army Commander sitting at his desk, seemingly immersed in paperwork. Monty did not look up but gestured to Evans to sit down and upon his doing so, greeted him with a warm smile and stated how pleased he was to meet him! The ice was broken and Montgomery repeated the invite given earlier by De Guingand to attend the victory celebrations on the next day and to meet the King, before mentioning Evans’ first official mission, which would be to fly Monty to Cairo in a couple of days time.

Monty was not an easy man to know or to work for and Evans would incur the great man’s displeasure quite early in their association, in fact on Monty’s first flight in the Theresa Leta.

In the next edition of this blog, we shall see how Captain Evans managed to unnerve the usually unflappable British General, as well as upsetting Monty's great rival, General George S Patton, during his tour as Monty's pilot.

Published Sources:

The Memoirs of Field Marshal The Viscount Montgomery of Alamein - Collins 1958

Unpublished Sources:

Unpublished Memoirs of the late Colonel Richard E Evans, USAF