|

| Gotha Terror by Ian Castle cover (author's photo) |

Wednesday, 4 December 2024

Gotha Terror: The Forgotten Blitz 1917-1918 by Ian Castle

Thursday, 15 February 2024

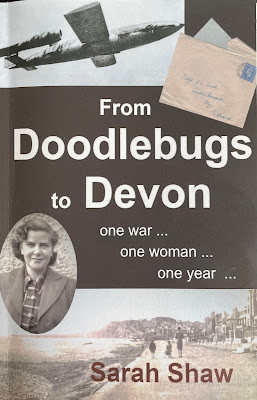

From Doodlebugs to Devon - by Sarah Shaw

|

| From Doodlebugs to Devon cover (author's photo) |

Monday, 22 January 2024

Book Review - "Unbroken Glory" The Great War Story of Anson Battalion, The Royal Naval Division by Dr Robert Wynn Jones

This is Dr

Jones’ second foray into the world of military history and as with his first

book, “Soldiers and Sportsmen All”, the subject matter has a definite family

connection for the author, as his paternal grandfather, Able Seaman Francis

Wynn Jones served in both the Nelson and Anson Battalions of the Royal Naval

Division, spending the final eight months of the war in captivity, having been

captured on 23 March 1918, during the German Spring Offensive.

The author

begins by explaining the raison d’etre of

the Royal Naval Division and telling us something of his paternal grandfather, who

in normal life was a Post Office clerk in London, although he hailed from

Llandrillo in North Wales.

The book

charts the formation of the Royal Naval Division, which immediately became

known to some as “Churchill’s Private

Army” or perhaps worse as the “Tuppeny

untrained rabble” and explains the makeup of the various battalions, all

named after Royal Navy heroes of the past and how, perhaps confusingly to those

on the outside, the men all retained their naval ranks, ensuring that Able

Seaman, Leading Stokers and Chief Petty Officers could be found far away from

their usual maritime locations!

A wider

description of the war on the Western Front follows, with interesting

comparisons of the arms, equipment and organisation of the combatant nations

involved, as well as a good description of how life on the Western Front would

have been for the typical British soldier in the dugouts and trenches along the

front line – “either frightened to death

or bored to tears” – as one contemporary account succinctly put it.

The bulk of

the remainder of the book is taken up with descriptions of the various actions

that the Division were involved with starting with the ultimately unsuccessful

attempt to defend Antwerp, followed by the Gallipoli and Salonika Campaigns,

before we return to the various campaigns on the Western Front that occupied

the Division for the remainder of the war, culminating in the German Spring

Offensive of 1918 and the Allied “Hundred Days” Offensive that resulted in the

ultimate German collapse. The author vividly describes not only the Anson

Battalion’s involvement but also the battles in the wider context of the war

and has drawn not only from War Diaries but also from contemporary publications

and letters from those involved.

The author

has visited many of the battlefields himself and as any of us who have trodden

the ground can testify, has found it often to be a profoundly moving

experience.

The book

concludes with an extensive and comprehensive series of maps, photographs and

biographical sketches of men from the Anson Battalion, as well as a chapter

covering the life of the author’s paternal grandfather (or “Taid) Francis Wynn Jones. Without wishing to give away too many “spoilers”,

we last heard of Wynn, as he was universally known, ending the war in captivity

but before this was confirmed, he had in fact been posted as “missing” on the Flesquieres-Havrincourt

Salient on 23 March 1918 and it was not until over a month later on 25 April,

that word was received that he was still alive and was being held in captivity.

The author’s

description of his grandfather as an elderly man, whom he regularly met during his

childhood in the late 1960s, is heart-warming and ends this book on a suitably

optimistic note.

As with this author's previous military history volume, this is a well-research and fascinating read which I have no

hesitation in recommending to you.

Available

from www.amazon.co.uk

RRP £9.99

softback,

pp 314

Wednesday, 15 November 2023

In Memoriam: Neil Bright 1958 - 2023

|

| Neil Bright guiding in Westminster during 2010 (author's image) |

Tuesday, 31 October 2023

Book Review: Streatham's 41

|

| Cover of Streatham's 41 (author's image) |

In mid-June 1944, Londoners could perhaps have been forgiven for thinking that the days of attacks on them from the air were a thing of the past but on 13 June, a new threat to their safety appeared in the form of the V-1, the first of Hitler’s Vergeltungswaffen or “Vengeance Weapons”. In excess of 2,400 of these early cruise missiles were to fall upon London in a campaign that was to last until early September 1944, in which the various neighbourhoods of south and southeast London bore the brunt,

The original edition of this account

was written by Kenneth Bryant, Senior District Air Raid Warden of the Metropolitan

Borough of Wandsworth and appeared in 1946 as a basic record of the forty-one

flying bombs that fell upon the south London suburb of Streatham. In 2019 an

updated and expanded edition was produced by the Streatham Society to mark the

75th anniversary of the campaign and which has recently been re-issued once

again.

This attractive A4 softback booklet

provides a detailed analysis of each of “Streatham’s 41” flying bombs, each one

accompanied by a map, as well as personal accounts from those affected by each

incident and where available, contemporary photographs of the aftermath of each

bomb.

In addition, there are useful and

informative chapters on the organisation of the ARP (Air Raid Precautions),

later the Civil Defence Service in general and in particular within the Borough

of Wandsworth. There is also a brief history and timeline of the V-1 offensive

and the counter-measures put in place, as well as an interesting chapter

covering the human cost of the campaign and financial cost of rebuilding in Streatham,

most notably the “pre-fabs” that sprung up across London as a temporary

solution to re-housing those who had been rendered homeless.

There is also a chapter on the design

of the V-1, which leads to my only minor gripe with the book, in so far that the

authors describe the propulsion system as a ram jet, whereas in fact the V-1s

were propelled by a pulse jet system, which gave rise to the peculiar rasping

sound made by the engine.

Overall though, this is an excellent

local history publication which should be of interest to Home Front historians

as well as those with a love of our capital city’s history.

Streatham's 41: The V-1 Flying Bomb Offensive as experienced in Streatham

Author: Kenneth Bryant (updated edition prepared by John W Brown)

Published

by The Streatham Society (www.streathamsociety.org.uk)

RRP £11.00

Softback,

pp 90

Tuesday, 20 June 2023

Old Palace School - the largest Fire Service tragedy on British soil

|

| The order of service for the ceremony (author's photograph) |

|

| The original plaque, now obscured from public view (author's photograph) |

|

| Old Palace School before the war (Firemen Remembered) |

|

| The grim task of recovery (Firemen Remembered) |

|

| Stephanie Maltman and the Rev'd Cathy Wyles (author's photo) |

|

| Fire Brigade guests, past and present (author's photo) |

Monday, 8 May 2023

The Joys of Guiding

One of the many joys of guiding is the "surprise factor" brought to the party by our guests - when starting out with a group, whether it be from the Army, RAF, a school or college group, overseas visitors or a home-based group of history lovers, one never knows what to expect and this certainly helps to keep me as the guide, on my toes!

|

| The Hungerford Bridge parachute mine made safe (author's collection) |

A recent walk with a London-based group of history enthusiasts brought one of the biggest and most pleasant surprises in my thirteen-year guiding "career".

The group's organiser had requested a bespoke walk starting at Hungerford Bridge, which for non-Londoners is a bridge that carries the railway from Charing Cross Station across the Thames and which also doubles up as a footbridge. To be brutally honest, this isn't the most picturesque part of London but is one which has a wartime history, so I had a suspicion that at least one member of the group might have a connection in some way.

So when the group met on a dank Sunday morning in March, I began by explaining the wartime history of Hungerford Bridge, which began on the night of 16/17 April 1941, when a parachute mine settled on to the tracks just outside the station. Incendiary bombs were also falling and had started a major fire in the signal cabin at the end of platform one, with the flames creeping towards the mine, which had failed to explode.

|

| Lieut. Cdr. Ernest Oliver "Mick" Gidden GC, RNVR (fotostock) |

As parachute mines were adapted anti-shipping weapons, they were always dealt with by the Royal Navy who had the necessary expertise to deal with them and accordingly, a team led by Lieutenant Commander Ernest "Mick" Gidden RNVR.

Gidden worked on the mine for over six hours, breaking it free from the live rail, from which it had welded itself and forcing it back into some sort of shape with a large hammer, so that he could unscrew the fuse from the weapon and in doing so, earned himself a George Cross into the bargain. While Gidden was working on the mine, he was aware of the large fire burning in the signal cabin and noticed that two Auxiliary Firemen were tackling the fires, seemingly oblivious to their own safety - he later spoke of these men thus:

“When I arrived at the incident on Hungerford Bridge I found about half a dozen firemen working within 15 feet of the unexploded mine. This had already lost its filling plate, exposing the explosive to the naked fire should it have reached it. Luckily for the bridge and several important Government offices the firemen were able to prevent this happening. I warned the men of their imminent peril but they seemed not to care a jot and I had to order them away. They left with great reluctance.”

The two firemen in question were Station Officer George Watling, a London Fire Brigade "regular" with 21 years service and Auxiliary Fireman Alf Blanchard, a chef in civilian life, who had joined the Auxiliaries shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939. The men were based at Holloway in North London and in keeping with the work of the Auxiliaries, had been summoned down from their usual base of operations to assist in Westminster.

|

| Auxiliary Fireman Alfred Blanchard BEM (Kevin Ireland) |

For their work on the night, Blanchard and Watling were awarded the British Empire Medal, which was gazetted on 3 October 1941.

After explaining this incident to the group and the subsequent near-destruction of the bridge in a V-1 incident in July 1944, one of the group stepped forward and informed me that he was Alf Blanchard's grandson and had some mementos of his late grandfather to show me.

Alf's grandson was called Kevin Ireland and produced Alf's B.E.M. as well as a souvenir that his grandfather had secured for himself once the mine had been made safe - this was a piece of one of the cables that suspended the mine from the parachute. For once in my life, I was speechless!

|

| Kevin Ireland with his grandfather's souvenirs (author's photograph) |

To say that I went into geek mode would be an understatement and many photographs were taken at the time and after the walk, when e-mail addresses were also exchanged.

|

| Close up of Alf's BEM (author's photograph) |

|

| Close up of Alf's BEM (author's photograph) |

|

| The section of parachute cable (author's photograph) |

|

| Alf's letter of release from the Fire Service (Kevin Ireland) |