|

| Winston Churchill in 1940 (IWM) |

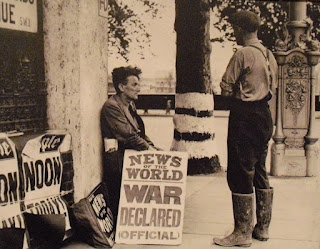

July 10th 1940 is the date most commonly agreed upon by historians as that which marks the opening of the First Phase of the Battle of Britain. It would be impossible in a blog of this nature to summarize the entire Battle in one post - after all, very many authors of high repute have devoted entire books to the subject and sometimes just to cover one day of the Battle, such was it's vastness in scope and it's importance to the survival of not only this country but the Free World as a whole.

In the coming weeks and months, we shall once again look at various aspects of the Battle of Britain in this blog but for now, let us examine the speech that introduced the phrase "Battle of Britain" into the consciousness of the British people and to World history. It is perhaps sometimes forgotten that it was Winston Churchill who first used the phrase in the closing part of a 36 minute speech to the House of Commons on June 18th 1940 on the state of the war following the imminent Fall of France. The date marked the 125th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo and when Churchill first used the phrase 'Battle of Britain', he could have only but hoped that the outcome of this battle would be as favourable as that which had taken place in 1815.

The speech is repeated verbatim below:

"I spoke the other day of the colossal military disaster which occurred

when the French High Command failed to withdraw the northern Armies from

Belgium at the moment when they knew that the French front was

decisively broken at Sedan and on the Meuse. This delay entailed the

loss of fifteen or sixteen French divisions and threw out of action for

the critical period the whole of the British Expeditionary Force. Our

Army and 120,000 French troops were indeed rescued by the British Navy

from Dunkirk but only with the loss of their cannon, vehicles and modern

equipment. This loss inevitably took some weeks to repair, and in the

first two of those weeks the battle in France has been lost. When we

consider the heroic resistance made by the French Army against heavy

odds in this battle, the enormous losses inflicted upon the enemy and

the evident exhaustion of the enemy, it may well be the thought that

these 25 divisions of the best-trained and best-equipped troops might

have turned the scale. However, General Weygand had to fight without

them. Only three British divisions or their equivalent were able to

stand in the line with their French comrades. They have suffered

severely, but they have fought well. We sent every man we could to

France as fast as we could re-equip and transport their formations.

I

am not reciting these facts for the purpose of recrimination. That I

judge to be utterly futile and even harmful. We cannot afford it. I

recite them in order to explain why it was we did not have, as we could

have had, between twelve and fourteen British divisions fighting in the

line in this great battle instead of only three. Now I put all this

aside. I put it on the shelf, from which the historians, when they have

time, will select their documents to tell their stories. We have to

think of the future and not of the past. This also applies in a small

way to our own affairs at home. There are many who would hold an inquest

in the House of Commons on the conduct of the Governments-and of

Parliaments, for they are in it, too-during the years which led up to

this catastrophe. They seek to indict those who were responsible for the

guidance of our affairs. This also would be a foolish and pernicious

process. There are too many in it. Let each man search his conscience

and search his speeches. I frequently search mine.

Of this I am quite sure, that if we open a quarrel between the past and

the present, we shall find that we have lost the future. Therefore, I

cannot accept the drawing of any distinctions between Members of the

present Government. It was formed at a moment of crisis in order to

unite all the Parties and all sections of opinion. It has received the

almost unanimous support of both Houses of Parliament. Its Members are

going to stand together, and, subject to the authority of the House of

Commons, we are going to govern the country and fight the war. It is

absolutely necessary at a time like this that every Minister who tries

each day to do his duty shall be respected; and their subordinates must

know that their chiefs are not threatened men, men who are here today

and gone tomorrow, but that their directions must be punctually and

faithfully obeyed. Without this concentrated power we cannot face what

lies before us. I should not think it would be very advantageous for the

House to prolong this Debate this afternoon under conditions of public

stress. Many facts are not clear that will be clear in a short time. We

are to have a secret Session on Thursday, and I should think that would

be a better opportunity for the many earnest expressions of opinion

which Members will desire to make and for the House to discuss vital

matters without having everything read the next morning by our dangerous

foes.

The disastrous military events which have happened during the past

fortnight have not come to me with any sense of surprise. Indeed, I

indicated a fortnight ago as clearly as I could to the House that the

worst possibilities were open; and I made it perfectly clear then that

whatever happened in France would make no difference to the resolve of

Britain and the British Empire to fight on, 'if necessary for years, if

necessary alone.' During the last few days we have successfully brought

off the great majority of the troops we had on the line of communication

in France; and seven-eighths of the troops we have sent to France since

the beginning of the war-that is to say, about 350,000 out of 400,000

men-are safely back in this country. Others are still fighting with the

French, and fighting with considerable success in their local encounters

against the enemy. We have also brought back a great mass of stores,

rifles and munitions of all kinds which had been accumulated in France

during the last nine months.

We have, therefore, in this Island

today a very large and powerful military force. This force comprises all

our best-trained and our finest troops, including scores of thousands

of those who have already measured their quality against the Germans and

found themselves at no disadvantage. We have under arms at the present

time in this Island over a million and a quarter men. Behind these we

have the Local Defence Volunteers, numbering half a million, only a

portion of whom, however, are yet armed with rifles or other firearms.

We have incorporated into our Defence Forces every man for whom we have a

weapon. We expect very large additions to our weapons in the near

future, and in preparation for this we intend forthwith to call up,

drill and train further large numbers. Those who are not called up, or

else are employed during the vast business of munitions production in

all its branches-and their ramifications are innumerable-will serve

their country best by remaining at their ordinary work until they

receive their summons. We have also over here Dominions armies. The

Canadians had actually landed in France, but have now been safely

withdrawn, much disappointed, but in perfect order, with all their

artillery and equipment. And these very high-class forces from the

Dominions will now take part in the defence of the Mother Country.

Lest

the account which I have given of these large forces should raise the

question: Why did they not take part in the great battle in France? I

must make it clear that, apart from the divisions training and

organizing at home, only 12 divisions were equipped to fight upon a

scale which justified their being sent abroad. And this was fully up to

the number which the French had been led to expect would be available in

France at the ninth month of the war. The rest of our forces at home

have a fighting value for home defence which will, of course, steadily

increase every week that passes. Thus, the invasion of Great Britain

would at this time require the transportation across the sea of hostile

armies on a very large scale, and after they had been so transported

they would have to be continually maintained with all the masses of

munitions and supplies which are required for continuous battle-as

continuous battle it will surely be.

Here is where we come to the

Navy-and after all, we have a Navy. Some people seem to forget that we

have a Navy. We must remind them. For the last thirty years I have been

concerned in discussions about the possibilities of oversea invasion,

and I took the responsibility on behalf of the Admiralty, at the

beginning of the last war, of allowing all regular troops to be sent out

of the country. That was a very serious step to take, because our

Territorials had only just been called up and were quite untrained.

Therefore, this Island was for several months particularly denuded of

fighting troops. The Admiralty had confidence at that time in their

ability to prevent a mass invasion even though at that time the Germans

had a magnificent battle fleet in the proportion of 10 to 16, even

though they were capable of fighting a general engagement every day and

any day, whereas now they have only a couple of heavy ships worth

speaking of-the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau. We are also told that the

Italian Navy is to come out and gain sea superiority in these waters.

If they seriously intend it, I shall only say that we shall be delighted

to offer Signor Mussolini a free and safeguarded passage through the

Strait of Gibraltar in order that he may play the part to which he

aspires. There is a general curiosity in the British Fleet to find out

whether the Italians are up to the level they were at in the last war or

whether they have fallen off at all.

Therefore, it seems to me

that as far as sea-borne invasion on a great scale is concerned, we are

far more capable of meeting it today than we were at many periods in the

last war and during the early months of this war, before our other

troops were trained, and while the B.E.F. had proceeded abroad. Now, the

Navy have never pretended to be able to prevent raids by bodies of

5,000 or 10,000 men flung suddenly across and thrown ashore at several

points on the coast some dark night or foggy morning. The efficacy of

sea power, especially under modern conditions, depends upon the invading

force being of large size; It has to be of large size, in view of our

military strength, to be of any use. If it is of large size, then the

Navy have something they can find and meet and, as it were, bite on.

Now, we must remember that even five divisions, however lightly

equipped, would require 200 to 250 ships, and with modern air

reconnaissance and photography it would not be easy to collect such an

armada, marshal it, and conduct it across the sea without any powerful

naval forces to escort it; and there would be very great possibilities,

to put it mildly, that this armada would be intercepted long before it

reached the coast, and all the men drowned in the sea or, at the worst

blown to pieces with their equipment while they were trying to land. We

also have a great system of minefields, recently strongly reinforced,

through which we alone know the channels. If the enemy tries to sweep

passages through these minefields, it will be the task of the Navy to

destroy the mine-sweepers and any other forces employed to protect them.

There should be no difficulty in this, owing to our great superiority

at sea.

Those are the regular, well-tested, well-proved arguments

on which we have relied during many years in peace and war. But the

question is whether there are any new methods by which those solid

assurances can be circumvented. Odd as it may seem, some attention has

been given to this by the Admiralty, whose prime duty and responsibility

is to destroy any large sea-borne expedition before it reaches, or at

the moment when it reaches, these shores. It would not be a good thing

for me to go into details of this. It might suggest ideas to other

people which they have not thought of, and they would not be likely to

give us any of their ideas in exchange. All I will say is that untiring

vigilance and mind-searching must be devoted to the subject, because the

enemy is crafty and cunning and full of novel treacheries and

stratagems. The House may be assured that the utmost ingenuity is being

displayed and imagination is being evoked from large numbers of

competent officers, well-trained in tactics and thoroughly up to date,

to measure and counterwork novel possibilities. Untiring vigilance and

untiring searching of the mind is being, and must be, devoted to the

subject, because, remember, the enemy is crafty and there is no dirty

trick he will not do.

Some people will ask why, then, was it that

the British Navy was not able to prevent the movement of a large army

from Germany into Norway across the Skagerrak? But the conditions in the

Channel and in the North Sea are in no way like those which prevail in

the Skagerrak. In the Skagerrak, because of the distance, we could give

no air support to our surface ships, and consequently, lying as we did

close to the enemy's main air power, we were compelled to use only our

submarines. We could not enforce the decisive blockade or interruption

which is possible from surface vessels. Our submarines took a heavy toll

but could not, by themselves, prevent the invasion of Norway. In the

Channel and in the North Sea, on the other hand, our superior naval

surface forces, aided by our submarines, will operate with close and

effective air assistance.

This brings me, naturally, to the great

question of invasion from the air, and of the impending struggle

between the British and German Air Forces. It seems quite clear that no

invasion on a scale beyond the capacity of our land forces to crush

speedily is likely to take place from the air until our Air Force has

been definitely overpowered. In the meantime, there may be raids by

parachute troops and attempted descents of airborne soldiers. We should

be able to give those gentry a warm reception both in the air and on the

ground, if they reach it in any condition to continue the dispute. But

the great question is: Can we break Hitler's air weapon? Now, of course,

it is a very great pity that we have not got an Air Force at least

equal to that of the most powerful enemy within striking distance of

these shores. But we have a very powerful Air Force which has proved

itself far superior in quality, both in men and in many types of

machine, to what we have met so far in the numerous and fierce air

battles which have been fought with the Germans. In France, where we

were at a considerable disadvantage and lost many machines on the ground

when they were standing round the aerodromes, we were accustomed to

inflict in the air losses of as much as two and two-and-a-half to one.

In the fighting over Dunkirk, which was a sort of no-man's-land, we

undoubtedly beat the German Air Force, and gained the mastery of the

local air, inflicting here a loss of three or four to one day after day.

Anyone who looks at the photographs which were published a week or so

ago of the re-embarkation, showing the masses of troops assembled on the

beach and forming an ideal target for hours at a time, must realize

that this re-embarkation would not have been possible unless the enemy

had resigned all hope of recovering air superiority at that time and at

that place.

In the defense of this Island the advantages to the

defenders will be much greater than they were in the fighting around

Dunkirk. We hope to improve on the rate of three or four to one which

was realized at Dunkirk; and in addition all our injured machines and

their crews which get down safely-and, surprisingly, a very great many

injured machines and men do get down safely in modern air fighting-all

of these will fall, in an attack upon these Islands, on friendly. soil

and live to fight another day; whereas all the injured enemy machines

and their complements will be total losses as far as the war is

concerned.

During the great battle in France, we gave very

powerful and continuous aid to. the French Army, both by fighters and

bombers; but in spite of every kind of pressure we never would allow the

entire metropolitan fighter strength of the Air Force to be consumed.

This decision was painful, but it was also right, because the fortunes

of the battle in France could not have been decisively affected even if

we had thrown in our entire fighter force. That battle was lost by the

unfortunate strategical opening, by the extraordinary and unforeseen

power of the armored columns, and by the great preponderance of the

German Army in numbers. Our fighter Air Force might easily have been

exhausted as a mere accident in that great struggle, and then we should

have found ourselves at the present time in a very serious plight. But

as it is, I am happy to inform the House that our fighter strength is

stronger at the present time relatively to the Germans, who have

suffered terrible losses, than it has ever been; and consequently we

believe ourselves possessed of the capacity to continue the war in the

air under better conditions than we have ever experienced before. I look

forward confidently to the exploits of our fighter pilots-these

splendid men, this brilliant youth-who will have the glory of saving

their native land, their island home, and all they love, from the most

deadly of all attacks.

There remains, of course, the danger of

bombing attacks, which will certainly be made very soon upon us by the

bomber forces of the enemy. It is true that the German bomber force is

superior in numbers to ours; but we have a very large bomber force also,

which we shall use to strike at military targets in Germany without

intermission. I do not at all underrate the severity of the ordeal which

lies before us; but I believe our countrymen will show themselves

capable of standing up to it, like the brave men of Barcelona, and will

be able to stand up to it, and carry on in spite of it, at least as well

as any other people in the world. Much will depend upon this; every man

and every woman will have the chance to show the finest qualities of

their race, and render the highest service to their cause. For all of

us, at this time, whatever our sphere, our station, our occupation or

our duties, it will be a help to remember the famous lines: He nothing

common did or mean, Upon that memorable scene.

I have thought it

right upon this occasion to give the House and the country some

indication of the solid, practical grounds upon which we base our

inflexible resolve to continue the war. There are a good many people who

say, "Never mind. Win or lose, sink or swim, better die than submit to

tyranny-and such a tyranny." And I do not dissociate myself from them.

But I can assure them that our professional advisers of the three

Services unitedly advise that we should carry on the war, and that there

are good and reasonable hopes of final victory. We have fully informed

and consulted all the self-governing Dominions, these great communities

far beyond the oceans who have been built up on our laws and on our

civilization, and who are absolutely free to choose their course, but

are absolutely devoted to the ancient Motherland, and who feel

themselves inspired by the same emotions which lead me to stake our all

upon duty and honor. We have fully consulted them, and I have received

from their Prime Ministers, Mr. Mackenzie King of Canada, Mr. Menzies of

Australia, Mr. Fraser of New Zealand, and General Smuts of South

Africa-that wonderful man, with his immense profound mind, and his eye

watching from a distance the whole panorama of European affairs-I have

received from all these eminent men, who all have Governments behind

them elected on wide franchises, who are all there because they

represent the will of their people, messages couched in the most moving

terms in which they endorse our decision to fight on, and declare

themselves ready to share our fortunes and to persevere to the end. That

is what we are going to do.

We may now ask ourselves: In what

way has our position worsened since the beginning of the war? It has

worsened by the fact that the Germans have conquered a large part of the

coast line of Western Europe, and many small countries have been

overrun by them. This aggravates the possibilities of air attack and

adds to our naval preoccupations. It in no way diminishes, but on the

contrary definitely increases, the power of our long-distance blockade.

Similarly, the entrance of Italy into the war increases the power of our

long-distance blockade. We have stopped the worst leak by that. We do

not know whether military resistance will come to an end in France or

not, but should it do so, then of course the Germans will be able to

concentrate their forces, both military and industrial, upon us. But for

the reasons I have given to the House these will not be found so easy

to apply. If invasion has become more imminent, as no doubt it has, we,

being relieved from the task of maintaining a large army in France, have

far larger and more efficient forces to meet it.

If Hitler can

bring under his despotic control the industries of the countries he has

conquered, this will add greatly to his already vast armament output. On

the other hand, this will not happen immediately, and we are now

assured of immense, continuous and increasing support in supplies and

munitions of all kinds from the United States; and especially of

aeroplanes and pilots from the Dominions and across the oceans coming

from regions which are beyond the reach of enemy bombers.

I do

not see how any of these factors can operate to our detriment on balance

before the winter comes; and the winter will impose a strain upon the

Nazi regime, with almost all Europe writhing and starving under its

cruel heel, which, for all their ruthlessness, will run them very hard.

We must not forget that from the moment when we declared war on the 3rd

September it was always possible for Germany to turn all her Air Force

upon this country, together with any other devices of invasion she might

conceive, and that France could have done little or nothing to prevent

her doing so. We have, therefore, lived under this danger, in principle

and in a slightly modified form, during all these months. In the

meanwhile, however, we have enormously improved our methods of defense,

and we have learned what we had no right to assume at the beginning,

namely, that the individual aircraft and the individual British pilot

have a sure and definite superiority. Therefore, in casting up this

dread balance sheet and contemplating our dangers with a disillusioned

eye, I see great reason for intense vigilance and exertion, but none

whatever for panic or despair.

During the first four years of the

last war the Allies experienced nothing but disaster and

disappointment. That was our constant fear: one blow after another,

terrible losses, frightful dangers. Everything miscarried. And yet at

the end of those four years the morale of the Allies was higher than

that of the Germans, who had moved from one aggressive triumph to

another, and who stood everywhere triumphant invaders of the lands into

which they had broken. During that war we repeatedly asked ourselves the

question: How are we going to win? and no one was able ever to answer

it with much precision, until at the end, quite suddenly, quite

unexpectedly, our terrible foe collapsed before us, and we were so

glutted with victory that in our folly we threw it away.

We do

not yet know what will happen in France or whether the French resistance

will be prolonged, both in France and in the French Empire overseas.

The French Government will be throwing away great opportunities and

casting adrift their future if they do not continue the war in

accordance with their Treaty obligations, from which we have not felt

able to release them. The House will have read the historic declaration

in which, at the desire of many Frenchmen-and of our own hearts-we have

proclaimed our willingness at the darkest hour in French history to

conclude a union of common citizenship in this struggle. However matters

may go in France or with the French Government, or other French

Governments, we in this Island and in the British Empire will never lose

our sense of comradeship with the French people. If we are now called

upon to endure what they have been suffering, we shall emulate their

courage, and if final victory rewards our toils they shall share the

gains, aye, and freedom shall be restored to all. We abate nothing of

our just demands; not one jot or tittle do we recede. Czechs, Poles,

Norwegians, Dutch, Belgians have joined their causes to our own. All

these shall be restored.

What General Weygand called the Battle

of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to

begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization.

Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our

institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must

very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in

this Island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may

be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit

uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United

States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into

the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more

protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace

ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British

Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still

say, 'This was their finest hour.' "

Churchill's speeches were sometimes know for their exaggeration but on this occasion, this was not the case and even 75 years on, the consequences for the Free World of a British defeat in the Battle do not bear thinking about. The Battle of Britain was to demonstrate to the rest of the World, especially to the United States that Britain was not defeated and that the hitherto invincible Nazi war machine could be defeated and stopped.

Even now, it is debatable as to whether Hitler really wanted an invasion of this country, or whether he felt he could bring Britain to heel through defeating the RAF and by the mere threat of invasion, installing a puppet government along the lines of Marshal Petain's Vichy regime in France, thus taking Britain out of the war and allowing him to concentrate his entire forces on Russia.

After the war, when German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was interrogated by the Russians whilst in British custody, he was asked which battle he viewed as being the most decisive to the eventual outcome of the war. The Russians were no doubt expecting him to say 'Stalingrad' but instead the old Field Marshall replied 'The Battle of Britain.' Perhaps von Rundstedt said this merely to spite the Russians but whatever the reason, it was not the answer they were looking for and they promptly ended their questioning and left!

Even today, 75 years after the event, the Battle of Britain evokes powerful emotions and talk of 'The Few', Spitfires, Hurricanes, Dowding, Park as well as the Commonwealth and overseas pilots, Kiwis, Canadians, Poles, Czechs and Americans amongst the 2,927 pilots of all Allied nationalities who flew in the Battle, of which 510 perished.

We should be eternally grateful to them all.

Published Sources:

The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain - Stephen Bungay, Aurum Press 2000

The Narrow Margin - Derek Wood with Derek Dempster - Tri Service Press 1990

Winston Churchill was a master of the use of the English language, whether in it's written or spoken form but of all of his inspirational wartime speeches, his address to the House of Commons on August 20th 1940, in which the above passage formed a part, is arguably his most famous. Certainly the phrase 'The Few' which was how Churchill described the RAF's pilots and aircrews, passed immediately into folklore.

Winston Churchill was a master of the use of the English language, whether in it's written or spoken form but of all of his inspirational wartime speeches, his address to the House of Commons on August 20th 1940, in which the above passage formed a part, is arguably his most famous. Certainly the phrase 'The Few' which was how Churchill described the RAF's pilots and aircrews, passed immediately into folklore.